Living in San Francisco, the pull of technology and the “next big thing” seems everywhere. From Facebook to Apple to insta-everything, there’s a steady stream of products promising to improve your life and ease your day-to-day. Yet there can be consequences, such as a loss of privacy — as the public has become all too aware of lately.

When it comes to technology, is the better question “Can it be done?” or “Should it be done?” And how do we reconcile the benefits of these advances with their potential for harm?

Such questions may seem uniquely modern, but the “Cult of the Machine” exhibit is a good reminder that in some ways, we’re simply looping the past. Showing at the de Young Museum in San Francisco until August 12, the exhibit pulls together works representing the Precisionist style, which was popular in the U.S. in the early to mid-1900s.

Precisionism arose during the Machine Age, which spanned the end of the 1800s through the mid-1900s. This era reflected a significant shift in technology, with the creation of new skyscrapers, bridges, and roads, and more modern methods of production and communication. There was a feeling of machination ushering in a new period of progress, where technology and order could bring mankind to great heights.

“It was not unusual, especially during the 1920s, for intellectuals and artists to speak of the machine as a religious force, a ‘new divinity,'” wrote Alan Trachtenberg in 1986 in the New York Times, in an interesting piece about the period’s art and design.

But there were also concerns about dehumanization, overcrowding in cities, and people losing their jobs to automation (sound familiar?). In the de Young exhibit, quotes representing different viewpoints are printed on the walls above the works. One from journalist Paul Rosenfeld in 1921 reflects this anxiety about science and technology:

“For a century, the machines have been … impoverishing the experience of humanity. Like great Frankenstein monsters … these vast creatures have suddenly turned on their masters, and made them their prey.”

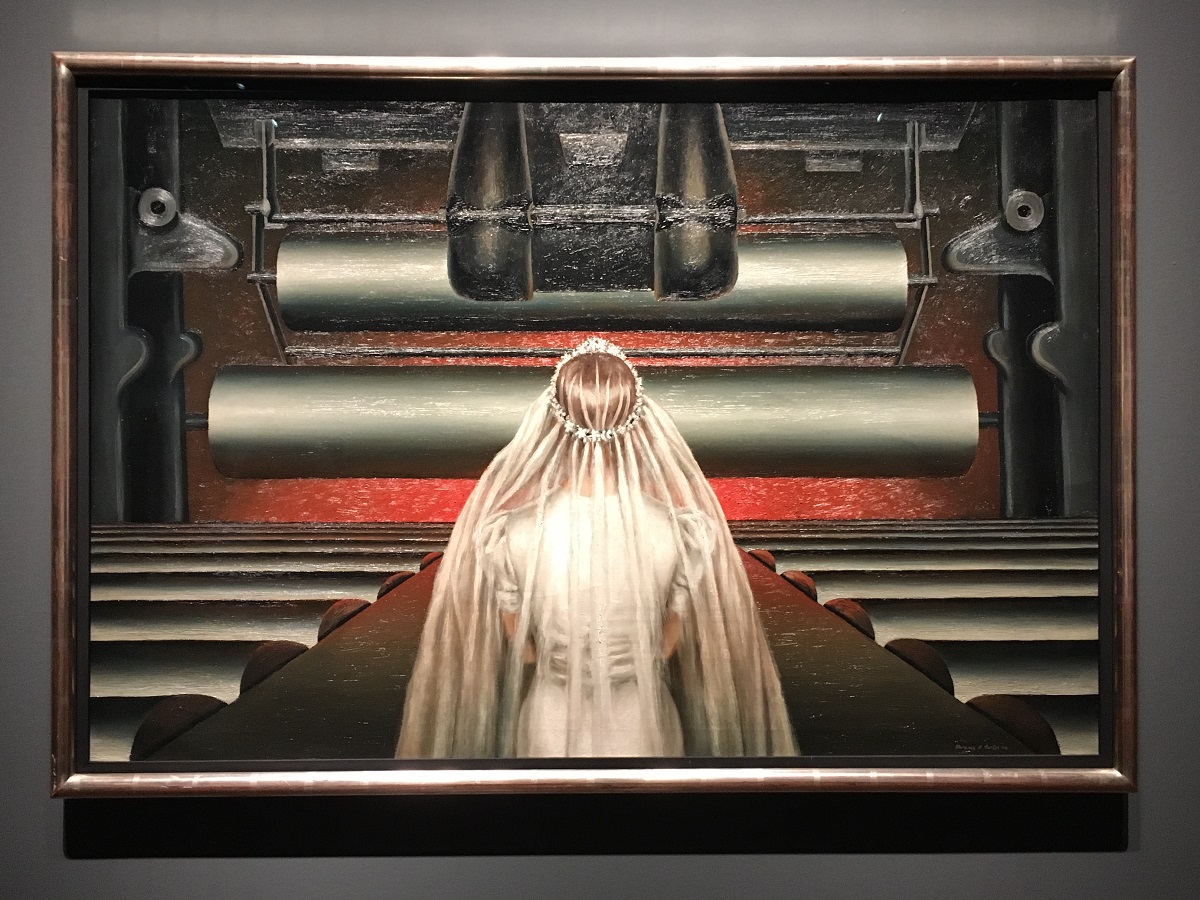

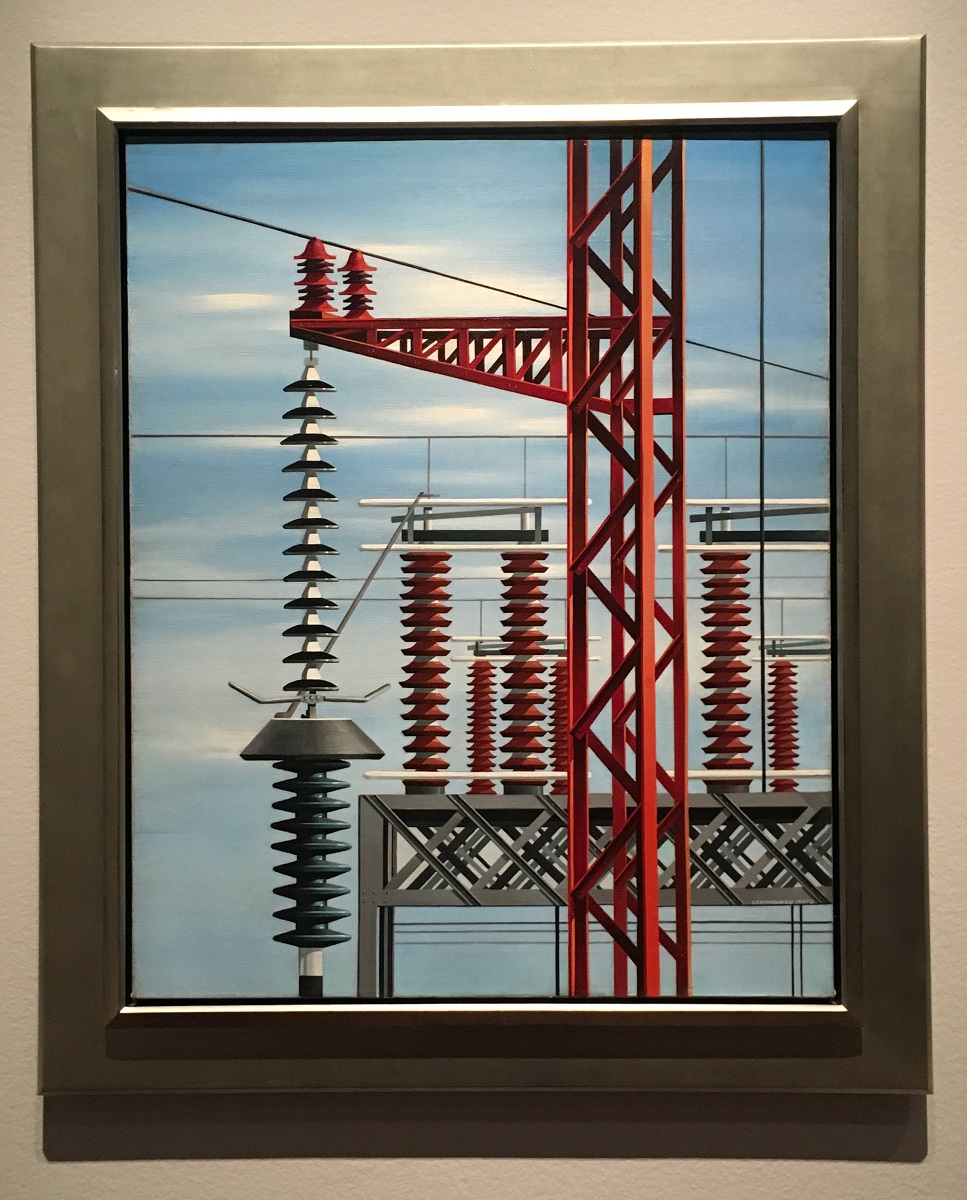

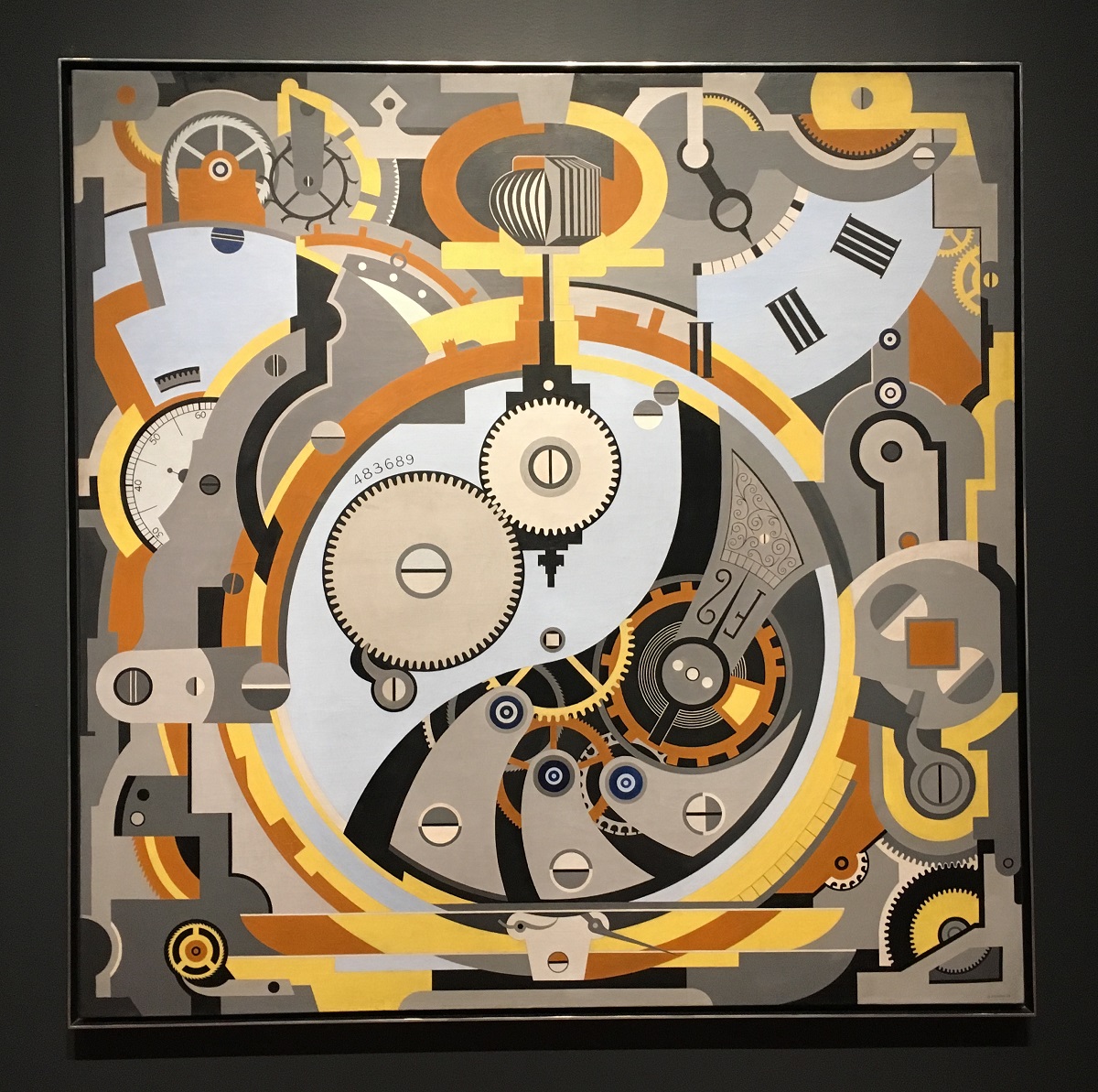

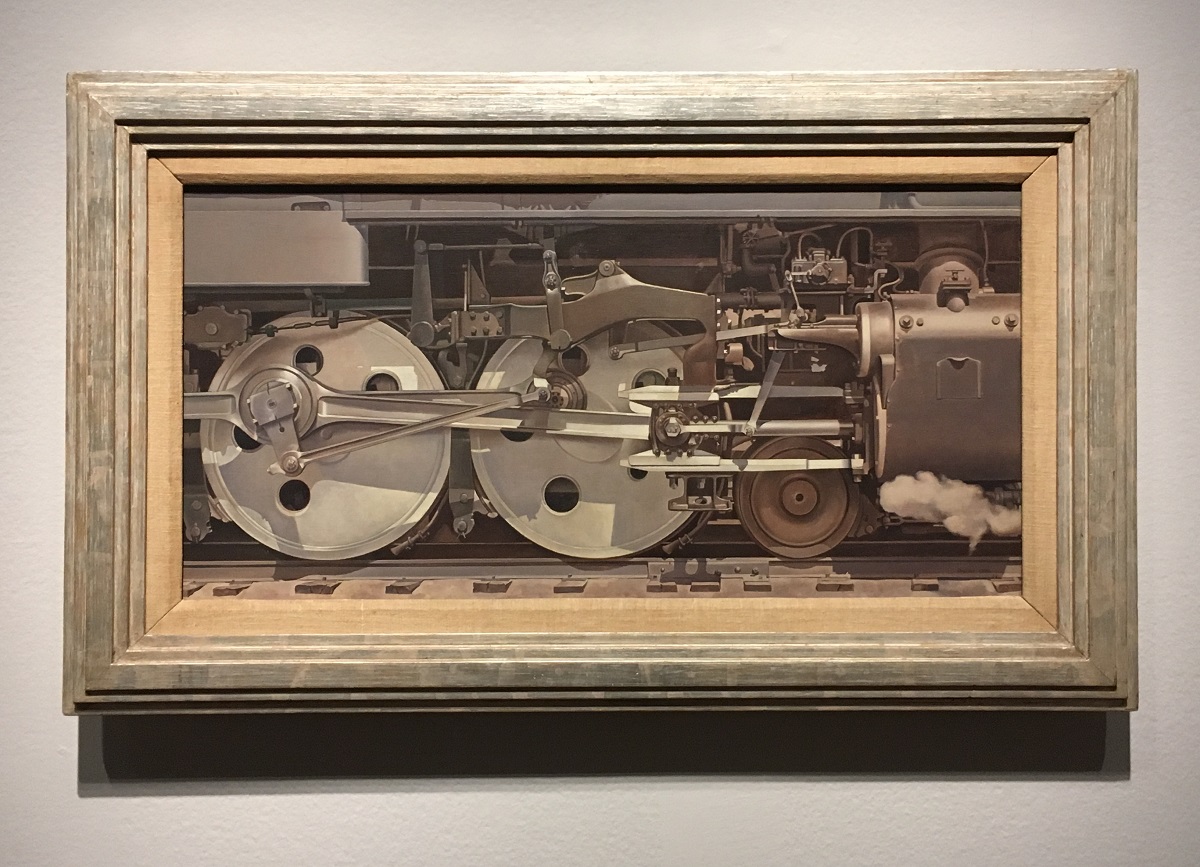

There seems to be some debate over which view, if any, various Precisionist artworks take — whether it’s a celebration of technology or anxiety over its effects. But in general they draw from the modernization of that time, with “structured, geometric compositions with smooth surfaces and lucid forms — reconciling the influence of avant-garde European art styles such as Purism, Cubism, and Futurism with American subjects ranging from the urban and the industrial to the rural,” the de Young explains.

Artists represented in the exhibit include Charles Sheeler, Charles Demuth, Louis Lozowick, Georgia O’Keeffe, George Copeland Ault, Gerald Murphy, and Elsie Driggs. Many of the pieces are city or industrial scenes — stark yet beautiful views of buildings, factories, or roads (often with nary a person in sight). Though not everything is urban: There are also works depicting rural areas, with barns and other scenery rendered in the same sparing style. Meanwhile, other pieces highlight mechanical structures, trains, and planes.

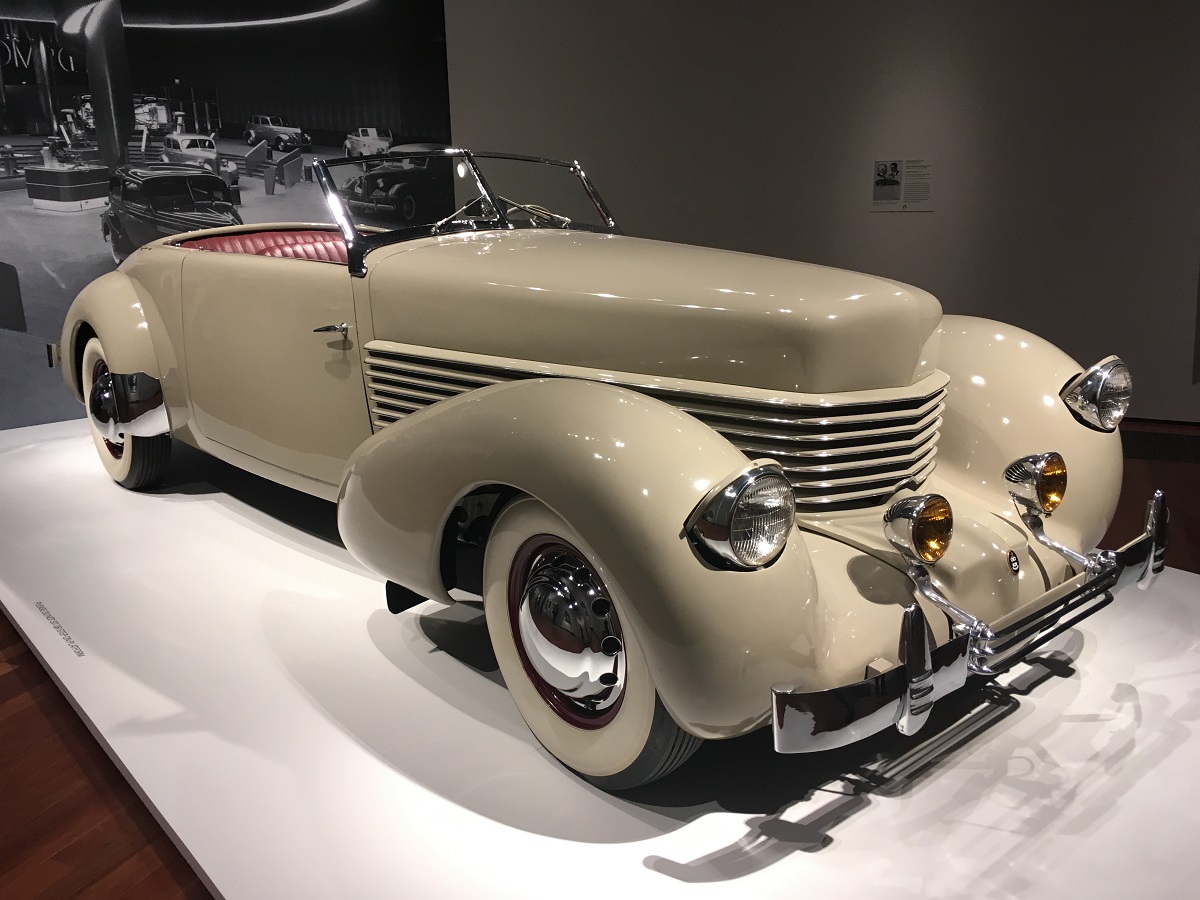

While much of the works are paintings and photographs, there are other types reflecting designs of the time, such as the Chanin Building gate from Rene Paul Chambellan, a “Skyscraper” bookcase from Paul Frankl, and a “Zeppelin Airship” cocktail shaker from J. A. Henckels Twin Works. For car buffs, the exhibit includes one of those as well: the Cord 812 Phaeton designed by Gordon Buehrig.

The museum has an excellent digital piece about the exhibit, and I came away from my visit agreeing with its conclusion — and thinking about the importance of art as a constant partner to progress, offering another view.

“Ultimately, despite the recurrent concerns — now with us for more than a century — about machine dominance and usurpation, we are left with the perhaps more burdensome realization that it is up to us to use technology in a manner that benefits society and positively contributes to human progress,” the de Young wrote.