When it comes to scientific imagery, where does documentation end and art begin? An exhibit underway in Pittsburgh touches on that question, featuring the work of British artist Rob Kesseler as well as 100-year-old botanical wall charts and historical glass models of marine organisms.

‘Worlds Within’ is being shown at Carnegie Mellon University, spread over two locations: at the Miller Gallery from September 23 through November 12 and at the Hunt Institute from the same opening date through December 15.

The Miller Gallery site is more focused on Kesseler’s micrographs, which explore the hidden interior world of seeds, pollen, and other plant life.

Rob Kesseler, “Scabiosa cretica.” Pincushion flower seed. Hand-colored micrograph, 2013. From: Fruit: Edible, inedible, incredible. Kesseler & Stuppy. Publ. Papadakis (via Miller Gallery).

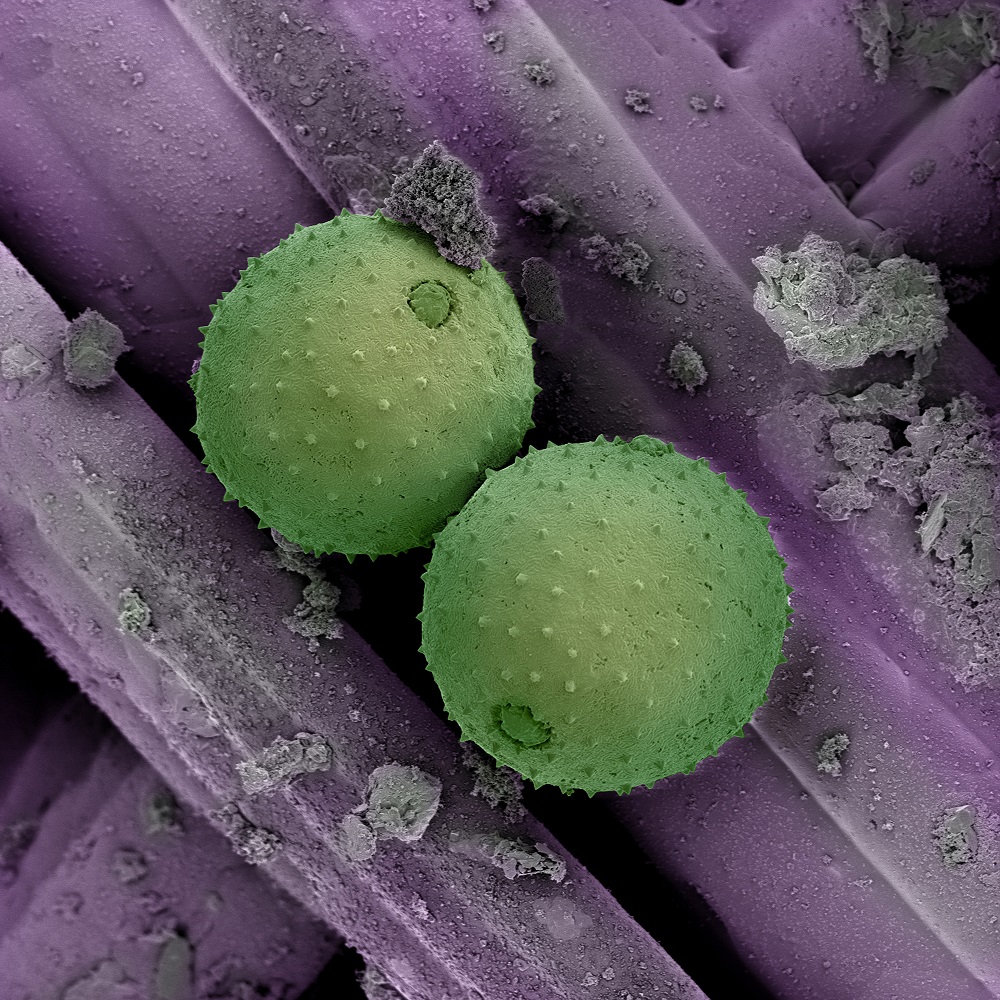

Rob Kesseler, “Poaceae.” Grass pollen grains on fibers of car filter. Hand-colored micrograph, 2008 (via Miller Gallery).

The Hunt Institute, meanwhile, provides a greater comparison between Kesseler’s work and the historical items, which include 19th-century botanical wall charts from the Botanische Wandtafeln series and glass models from father and son Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka.

“The graphic impact of historical instructive botanical wall charts and models alongside monumentalized, hand-colored botanical micrographs by Rob Kesseler creates a remarkable visual bridge between the conventional purpose of scientific illustration as used in educational materials and the aesthetic interpretation of scientific imagery in contemporary art,” the exhibit description states.

Creativity and microscopy

Kesseler, a visual artist and professor at Central Saint Martins, has been working with scientists at Kew Royal Botanic Gardens in the U.K. since the late ’90s, exploring the creative potential of microscopic material (as he explains in the video “Art, Science and the Artisan“). Building upon a longtime interest in microscopy, he initially reached out to scientists at Kew and received a response from botanist Madeline Harley, head of the pollen research unit.

“She invited me in, and she showed me her images, which were stunning … and she trained me on microscopes, and then it really snowballed from there,” he said.

Rob Kesseler, “Citrus hystrix.” Kaffir lime, longitudinal section through flower bud. Hand-colored micrograph, 2008. From: Fruit: Edible, inedible, incredible. Kesseler & Stuppy. Publ. Papadakis (via Miller Gallery).

Rob Kesseler, “Viburnum.” Stellate leaf hairs. Hand-colored micrograph, 2008 (via Miller Gallery).

Kesseler said he was struck by the beauty and complexity of such small yet essential parts of nature. His inspiration also came from an appreciation of books like Art Forms in Nature, a collection of prints from 19th-century biologist and artist Ernst Haeckel.

“I was trying to do something which built on that tradition of artists and scientists visualizing nature to capture a wider audience,” he said.

His process of creating these images involves valuable time spent outside observing specimens, along with the effort spent over the microscope. Kesseler also uses various programs to reconstruct images and apply color and other techniques, as part of the transition from scientific representation into art, as he explained in infocus magazine when discussing the works in his book Fruit:

The final result is one in which the manipulative hand of the artist, aided by the creative application of diverse technologies, has intervened to produce an image autonomous from science but with that disturbing sense of hyperreality that science can evoke. It is this other worldliness that distinguishes the result from a functional specimen, however alluring it might be. Historically the work of the finest botanical artists has risen above the mere recording of specimens for scientific purposes, and in creating this … I am striving towards communicating the same sense of wonder within a contemporary context.

Drawings, models from the past

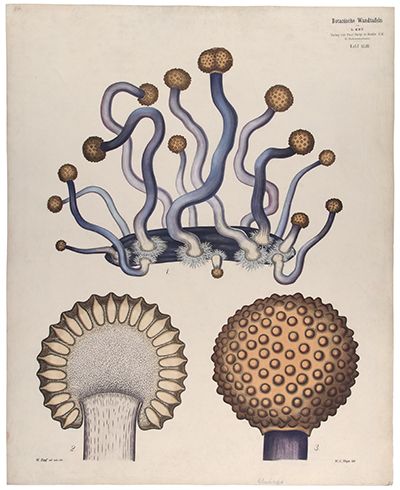

Continuing the theme of botanical works in the exhibition (albeit moving back about a hundred years) are items from Botanische Wandtafeln, a series of lithographs issued by German botanist Carl Ignaz Leopold Kny. The 120 instructional wall charts in the series were created by several artists and published from 1874 to 1911, according to the Hunt Institute.

“Fungal development in Claviceps purpurea (Fries) Tulasne, Clavicipitaceae,” color lithograph by W. A. Meyn (fl.1874-1911), 81.5 × 66 cm, after an original by W. Zopf (fl.ca.1874-1911) for Carl Ignaz Leopold Kny (1841-1916), Botanische Wandtafeln (Berlin, Paul Parey, 1874–1911, pl. 43), HI Art accession no. 6699.043 (via Hunt Institute).

The large charts had the practical purpose of being displayed in classrooms to teach students about botany. However, other methods eventually took over, and the wall charts fell out of favor. The lithographs continue to be useful sources of information, though, as well as interesting in terms of their historical role in scientific education, the institute noted.

Finally, the botanical wall charts and Kesseler’s images are complemented by historical works of another type: glass models of sea organisms. The models are of invertebrates from father and son Czech glass artists Leopold (1822-1895) and Rudolf Blaschka (1857-1939), as well as glacite works from New York artist Edwin H. Reiber (1881-1967).

Such models reflected a growing interest in science and natural history at that time, leading to new museums available to the public, as Cornell University explains. However, there was a dilemma: How do you preserve and show invertebrates — without them eventually disintegrating into something much less fun to observe? Enter glass models, of which the Blaschkas created thousands for institutions worldwide.

Example of Blaschka glass model. Glasmodell einer Ohrenqualle, Museum der Universität Tübingen, Valentin Marquardt. By KarinaDipold (own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0], via Wikimedia Commons.

The Blaschkas have an interesting backstory, which is told in depth by the Corning Museum of Glass. More information about Kesseler and his significant prior work is also available at robkesseler.co.uk.

Regarding the fields of art and science, Kesseler said in “Art, Science and the Artisan” that there’s more of an awareness now of the importance of collaborating across disciplines. Yet there’s still more that can be done.

“We don’t talk across disciplines anywhere near as much as we should do,” he said.